To compare the cardiorespiratory responses during deep water running with and without displacement at different cadences.

MethodsTwelve young women performed deep water running with and without displacement during 4 min at three separate cadences: (a) 60 bpm; (b) 80 bpm; and (c) 100 bpm. The heart rate (HR), ventilation (Ve) and oxygen uptake (VO2) were collected in the last minute of each test. Two-way ANOVA for repeated measures was used with Bonferroni's post hoc test (p < 0.05) to compare variables.

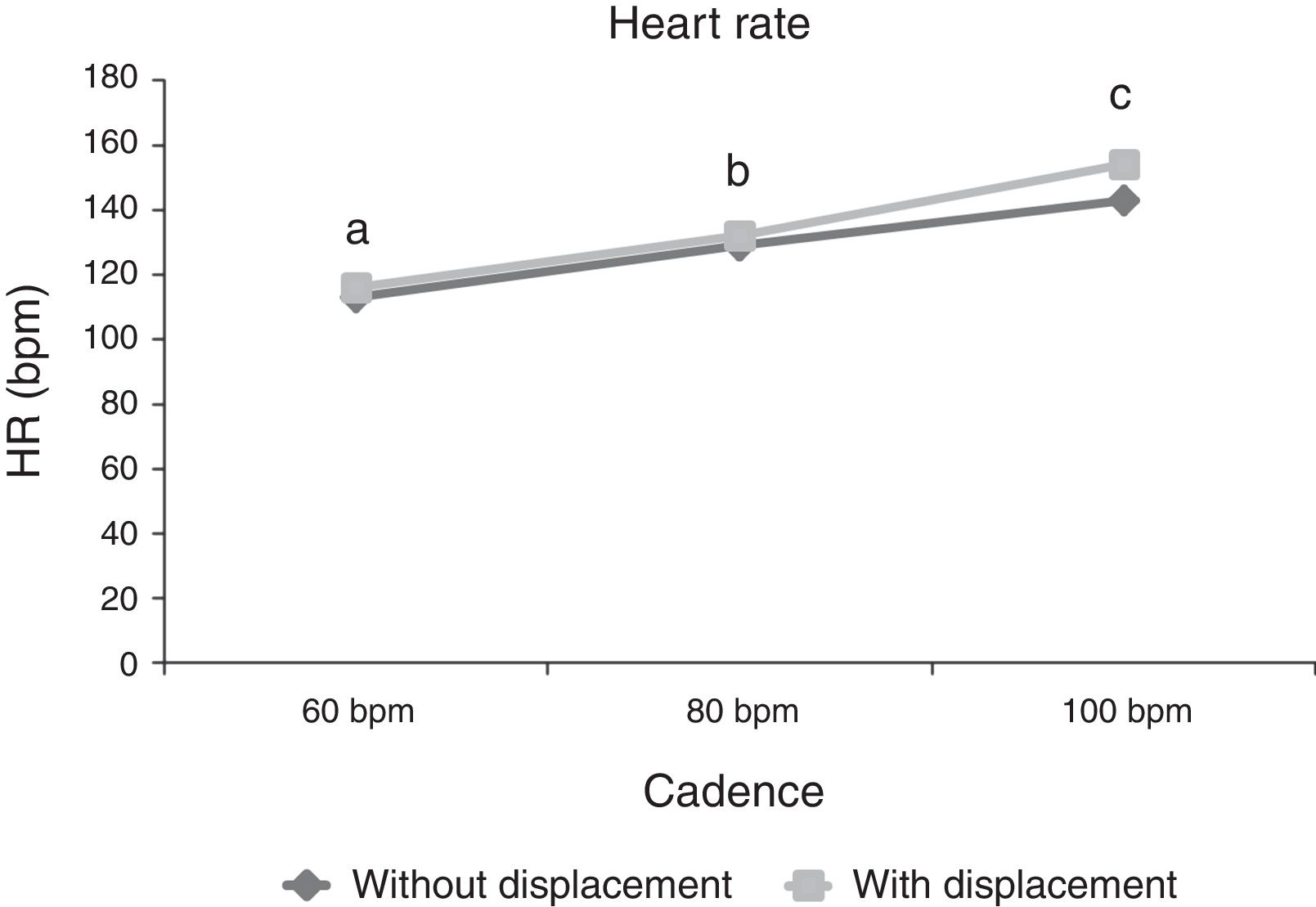

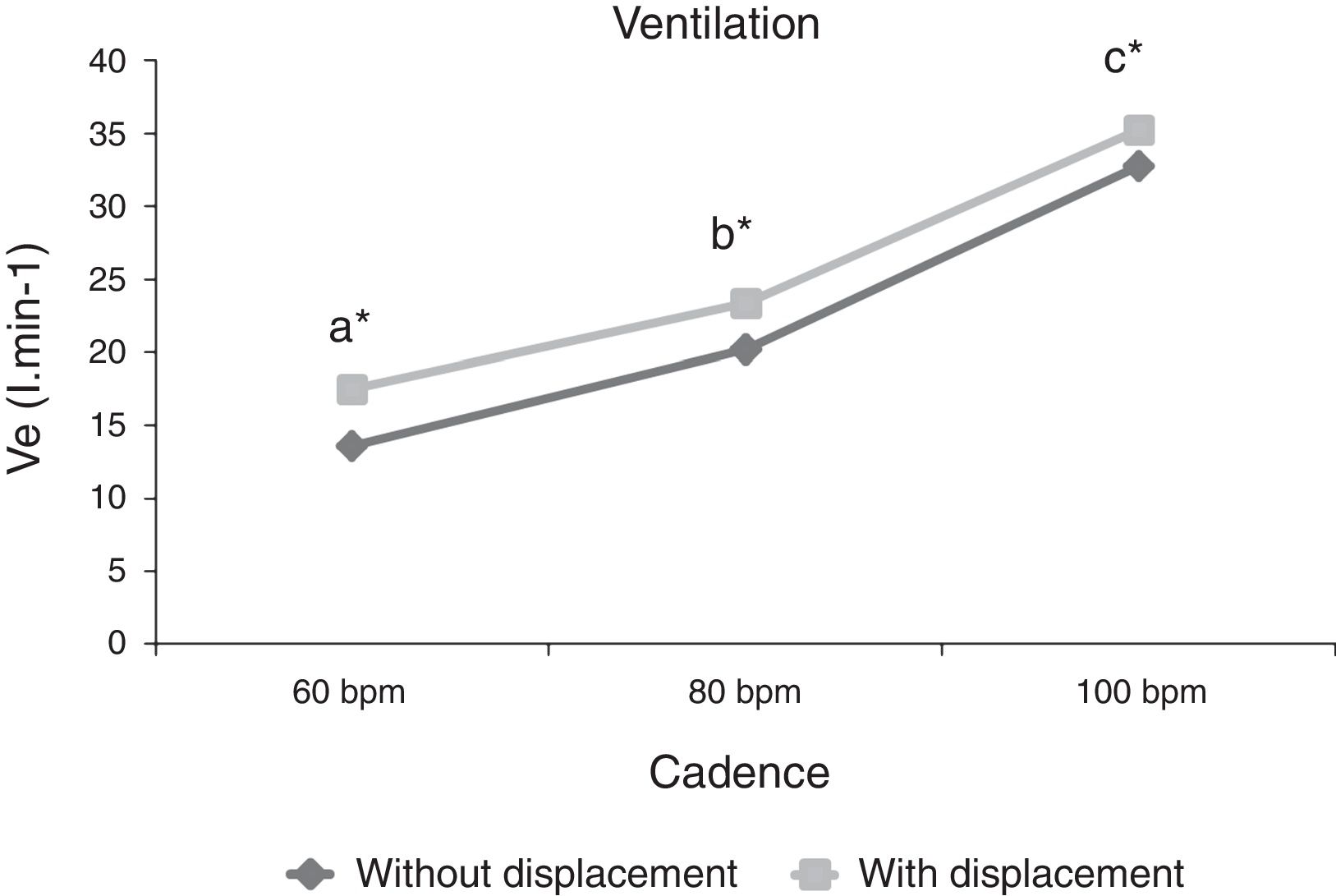

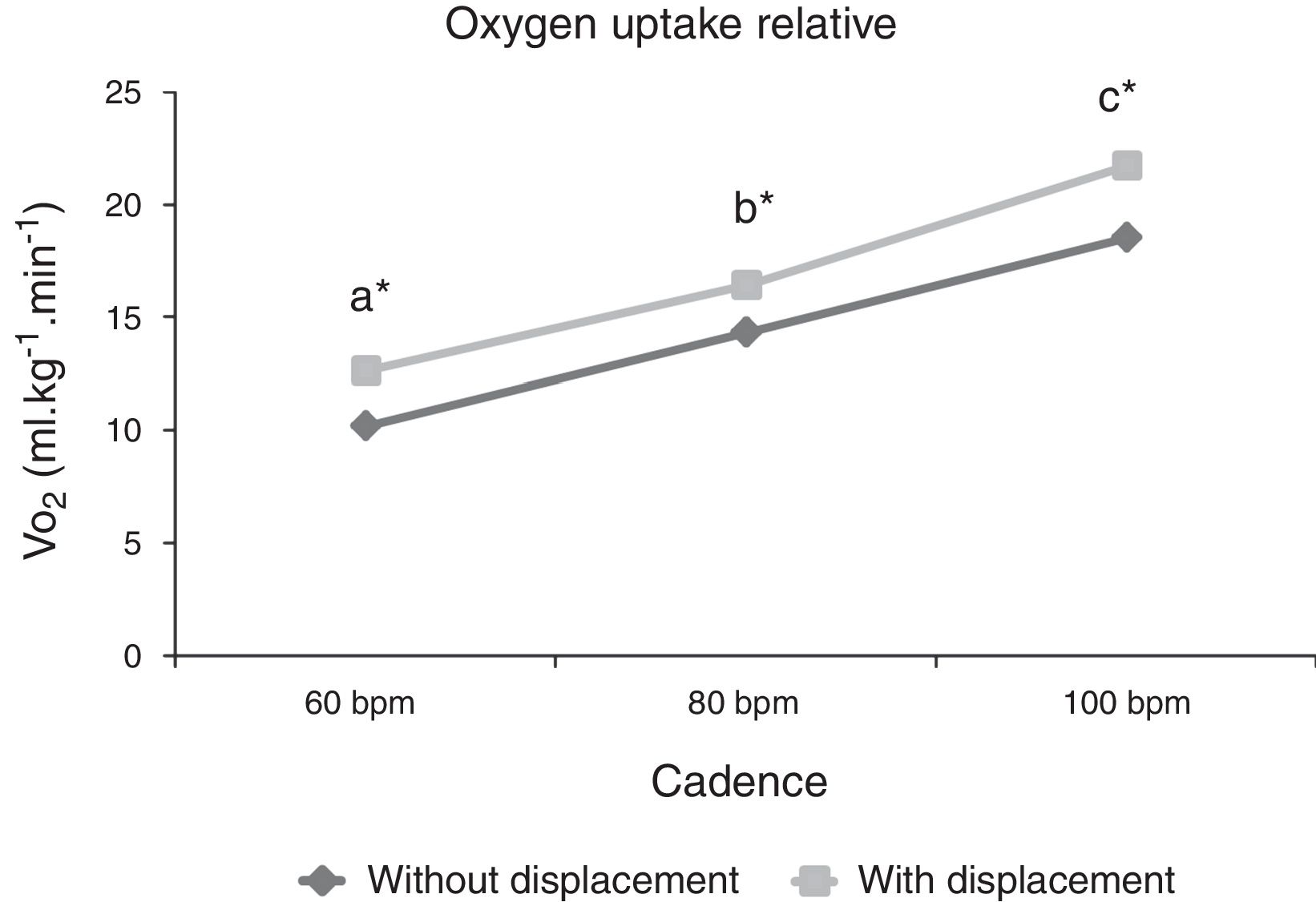

ResultsThe results showed a significant increase in all variables as the cadence increased (HR: p < 0.001; Ve: p < 0.001; VO2: p < 0.001). In addition, the VO2 and Ve values were significantly higher for deep water running with displacement compared to running without displacement (VO2: p = 0.047; Ve: p = 0.007). However, there was no significant difference in HR with and without displacement (p = 0.065).

ConclusionsThe results indicate that the increase in both cadence and displacement results in significant cardiorespiratory responses as a result of deep water running. This finding is important for adapting exercise prescription to the goals of participants.

comparar las respuestas cardiorrespiratorias durante la carrera en aguas profundas con y sin desplazamiento horizontal y a diferentes cadencias.

MétodoDoce mujeres jóvenes realizaron la carrera en aguas profundas con y sin desplazamiento durante cuatro minutos a tres cadencias diferentes: a) 60 bpm, b) 80 bpm, y c) 100 bpm. La frecuencia cardíaca (FC), la ventilación (VE) y el consumo de oxígeno (VO2) se recogieron en el último minuto de cada prueba. ANOVA de dos vías para medidas repetidas con post hoc de Bonferroni (p < 0,05) se utilizaron para comparar las variables.

ResultadosLos resultados mostraron un aumento significativo en todas las variables con el aumento de la cadencia (FC: p < 0,001; Ve: p < 0,001; VO2: p < 0,001). Además, los valores de VO2 y Ve fueron significativamente mayores para la carrera en aguas profundas que se ejecuta con desplazamiento en comparación con la realizada sin desplazamiento (VO2: p = 0,047; Ve: p = 0,007). Sin embargo, no hubo diferencia significativa en FC con y sin desplazamiento (p = 0,065).

ConclusionesLos resultados indican que el incremento de la cadencia y el desplazamiento proporcionan importantes respuestas cardiorrespiratorias en la carrera en aguas profundas. Este hallazgo es importante para la adaptación de la prescripción de ejercicio de acuerdo con los objetivos de los participantes.

comparar as respostas cardiorrespiratórias durante corrida em piscina funda profunda com e sem deslocamento horizontal em diferentes ritmos.

MétodosDoze mulheres jovens realizaram corrida aquática com e sem deslocamento durante quatro minutos, em três ritmos distintos: a) 60 bpm; b) 80 bpm; e c) 100 bpm. A frequência cardíaca (FC), ventilação (VE) e o consumo de oxigênio (VO2) foram coletados no último minuto de cada teste. Two-way ANOVA para medidas repetidas foi utilizada com o teste post hoc Bonferroni's (p < 0,05) para comparar as variáveis.

ResultadosOs resultados mostraram aumentos significativos em todas as variáveis conforme o aumento do ritmo (FC: p < 0,001; VE: p < 0,001; VO2: p < 0,001). Além disso, os valores de VO2 e VE foram significativamente maiores para corrida aquática com deslocamento em relação à corrida sem deslocamento (VO2: p = 0,047; VE: p = 0,007). No entanto, não houve diferença significativa na FC com e sem deslocamento (p = 0,065).

ConclusãosOs resultados indicam que o aumento do ritmo e deslocamento proporcionam importantes respostas cardiorrespiratórias na corrida em piscina funda. Este achado é importante para adaptar a prescrição de exercícios conforme os objetivos dos participantes.

The study of cardiorespiratory responses in aquatic exercise has gained attention in recent years, mainly to improve the prescription of these activities. Swimming, water-based exercise and deep water running can be highlighted as activities developed in an aquatic environment. Such activities have been recommended due to their physical fitness benefits, 1 lower cardiovascular demand 2,3 and reduced impact on the joints of the lower limbs. 4–9

Deep water running is performed with the aid of a floatation vest that keeps the individual upright and does not allow the feet to rest on the bottom of the pool. 10 This exercise can be performed with or without displacement. Moreover, deep water running can be an effective form of cardiovascular conditioning for both injured athletes and individuals who need aerobic exercise without impact on the joints of the lower limbs. 11

Several studies have shown that exercise involving vertical displacement, such water-based exercise, and an increase in cadence result in a rise in angular velocity and, consequently, oxygen uptake (VO2) and heart rate (HR). 1,12–15 These responses also have been found with increasing linear velocity in horizontal displacement exercises, such as water walking. 16–20 However, in deep water running, it is not yet clear which factors directly influence the increase in cardiorespiratory responses at submaximal intensities. According to studies previously cited, the increase in exercise intensity, either by cadence (angular velocity) or speed (linear velocity), maximizes the cardiorespiratory response, largely because the drag force increases with the increase in velocity. 21

Furthermore, an increase in the projected frontal area increases the resistance of the movement, contributing to elevated cardiorespiratory responses. In deep water running, resistance can be increased by using different arm movements 22 and alternating running with and without displacement. 3 In this way, Kanitz et al. 3 compared deep water running with and without displacement in a submaximal cadence of 80 bpm. The authors observed no significant differences in VO2, energy expenditure (EE) or perceived exertion (PE) and stated that the low linear velocity of horizontal displacement at a submaximal cadence (80 bpm) may have contributed to the resistance, which was maximized to influence other variables.

Although there is interest in evaluating cardiorespiratory responses during deep water running, there are few studies that have analyzed responses to different intensities and execution forms. There are many factors that influence cardiorespiratory variables during water immersion, causing different physiological responses or varying interpretations in study conclusions. It is important to highlight these influences so that fitness professionals can appropriately prescribe exercises performed in an aquatic environment.

Due to the growing number of participants in varying types of water exercise, it is necessary to understand the physiological responses so that water exercise programs, such as deep water running, can be adapted to the goals of the participants. Thus, the aim of the present study was to compare cardiorespiratory responses for young women during deep water running with and without displacement at different cadences.

Methods SubjectsThe sample was composed of twelve young, physically active women between 19 and 26 years of age. Subjects were selected through verbal invitation to scholarship holders within a community project coordinated by the School of Physical Education at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (ESEF/UFRGS). The sample size was calculated in PEPI (Version 4.0) at a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 90%. Subject characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) of physical characteristics, including age, body mass, height, body mass index (BMI), maximal heart rate (HRmax) and maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max).

| Mean | ±SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 23.25 | 1.96 |

| Body mass (kg) | 57.91 | 7.13 |

| Height (m) | 161.46 | 5.57 |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 20.98 | 5.09 |

| HRmax (bpm) | 190.00 | 5.00 |

| VO2max (ml kg−1 min−1) | 34.83 | 5.15 |

All participants read and signed the informed consent form. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS: No. 2008192). For inclusion in the sample, the candidates had to be healthy, to be non-smokers, and not currently be taking medications. In addition, all subjects were participating in a community project of deep water running for at least six months as teachers and/or instructors of this modality.

Experimental proceduresAll subjects attended a session where they signed the informed consent form and completed the personal data form, and both weight and height were recorded. In addition, a familiarization session and two exercise sessions were scheduled for each subject. The order of the exercise sessions was randomized, and, for every subject, a minimum of 48 h was scheduled between each session.

All sessions were held in the Swimming Center at Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) in a deep pool measuring 16 m wide, 25 m long and 2 m deep. The water was maintained at a temperature of 30 °C, which is considered thermally neutral for water-based exercise. 23 In the familiarization session, the correct technique for deep water running with the floatation vest in two execution forms (with and without displacement) was demonstrated well as was the cadences used in the tests, Borg's Scale (6–20) and the neoprene mask used for gas collection.

The exercise sessions consisted of performing deep water running with and without horizontal displacement for 4 min at three submaximal cadences (60, 80 and 100 bpm), which were reproduced with the aid of a digital metronome (model MA-30, KORG). The cadence order and execution form (with and without displacement) were randomized. The test without displacement was performed with one end of a cable attached to the subject through the floatation vest and the other end fixed at the pool's edge. We asked the subjects to maintain stride amplitude during the entire test, and subjects were assisted through visual feedback from the researcher. The participants were asked not to eat or consume stimulants during the 3 h prior to each test. In addition, subjects were asked not to practice heavy physical exercise 12 h prior to the tests. 24

Before each test, subjects remained at rest in a supine position for 30 min to assess the at-rest VO2. To ensure that all subjects started the tests with the same metabolic status, the values of the initial at-rest VO2 were used as a reference point for the remaining VO2 values during the test. Following the rest period, the first exercise test began at a determined cadence and execution form. The subject then rested long enough for the VO2 values to lower to that of the initial at-rest VO2. Exercise was then performed again using the same execution form, but a different cadence. The subject rested again, and then, the final exercise test was performed using the same execution form and the last cadence (Fig. 1).

HR, VO2 and ventilation (Ve) were collected every 10 s during the two test sessions. A frequency meter (Polar, model FS1) was used to measure HR. A portable gas analyser (INBRAMED, model VO2000) was used to determine VO2 and Ve. The equipment was calibrated according to the manufacturer's instructions prior to each collection. Immediately following the end of the exercise, RPE was collected according to the Borg-6-20 RPE scale.

Data treatmentDuring the rest period prior to each test, the mean value obtained for the last 3 min of VO2 was calculated. For each test, the average of the VO2, Ve and HR values were obtained between the third and fourth minutes.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were used for data analysis, and the data are reported as the mean ± SD. The Shapiro–Wilk test for normality was used. Two-way ANOVA for repeated measures and Bonferroni's post hoc test were used to identify whether each subject started the exercise tests with cardiorespiratory responses similar to those at rest (factors were moment and day) and to determine significant differences in the cardiorespiratory variables (factors were execution form and cadence). Statistical significance was established as α = 0.05, and the SPSS (Version 20.0) statistical package was employed.

ResultsThe resting VO2 values are shown in Table 2. The results showed that the individuals began the exercise sessions with a similar metabolic status, indicating that the magnitude of the responses found during the exercise tests can be attributed to the effort required to complete them.

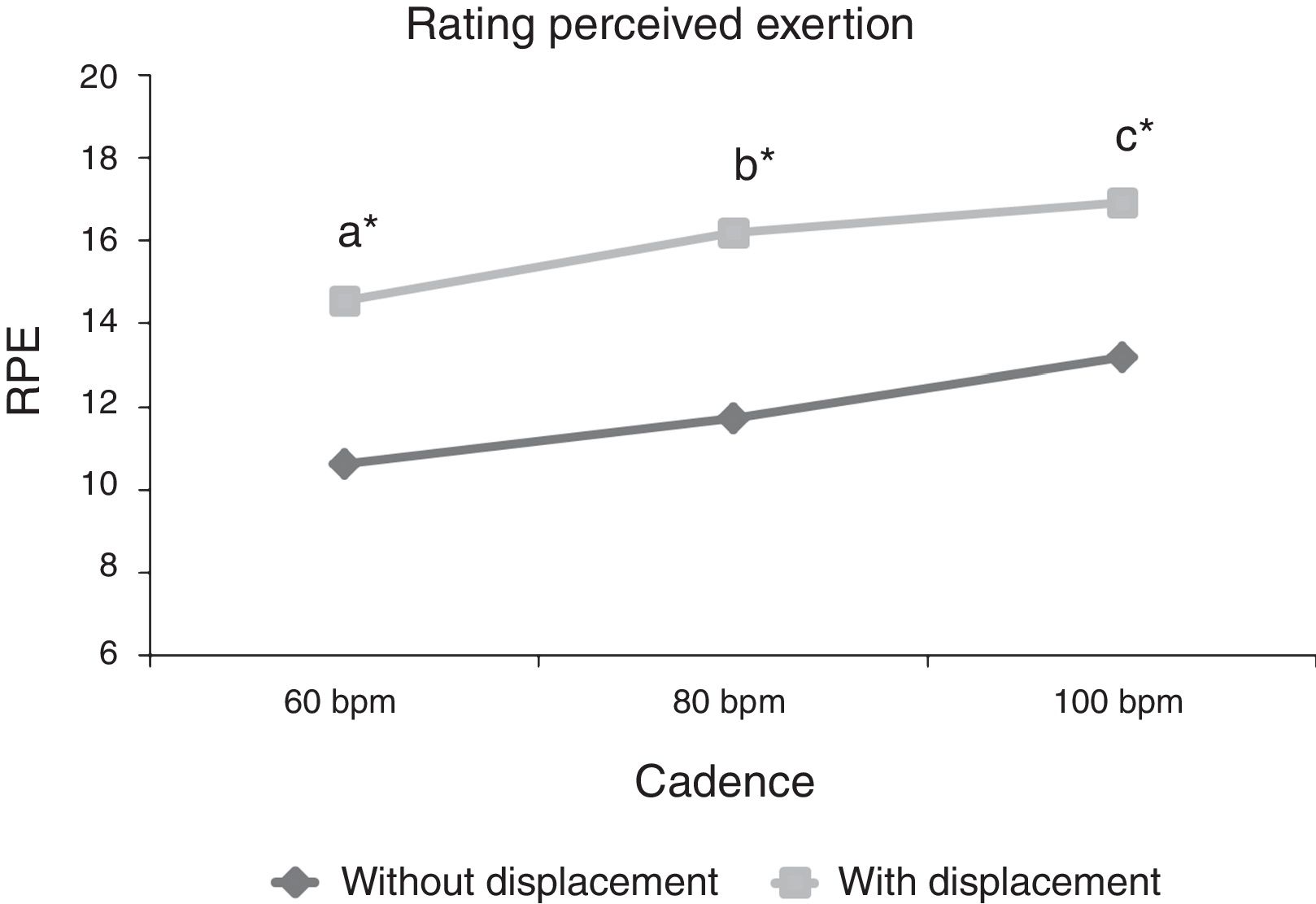

The pattern of the cardiorespiratory variables during exercise performed in both execution forms at each cadence is presented in Figs. 2–6. According to the results, we can note that, with the increase in cadence, there is a significant increase in HR (p < 0.001), Ve (p < 0.001), RPE (p < 0.001) and both absolute (p < 0.001) and relative VO2 (p < 0.001). Furthermore, we found significantly higher values for Ve (p = 0.007), PE (p = 0.054) and both absolute (p = 0.047) and relative VO2 (p = 0.028) during deep water running with displacement when compared to running without displacement. There was no significant difference between the two execution forms (p = 0.065) for HR.

Heart rate (HR) behavior at different cadences (60, 80 and 100 bpm) and different execution forms (with and without displacement). Different letters represent statistically significant difference between cadences for both execution forms (p ≤ 0.05). *represents statistically significant difference between execution forms (p ≤ 0.05).

Ventilation (Ve) behavior at different cadences (60, 80 and 100 bpm) and different execution forms (with and without displacement). Different letters represent statistically significant difference between cadences for both execution forms (p ≤ 0.05). *represents statistically significant difference between execution forms (p ≤ 0.05).

Absolute oxygen uptake (VO2) behavior at different cadences (60, 80 and 100 bpm) and different execution forms (with and without displacement). Different letters represent statistically significant difference between cadences for both execution forms (p ≤ 0.05). *represents statistically significant difference between execution forms (p ≤ 0.05).

Relative oxygen uptake (VO2) behavior at different cadences (60, 80 and 100 bpm) and different execution forms (with and without displacement). Different letters represent statistically significant difference between cadences for both execution forms (p ≤ 0.05). *represents statistically significant difference between execution forms (p ≤ 0.05).

Rating perceived of exertion (RPE) behavior at different cadences (60, 80 and 100 bpm) and different execution forms (with and without displacement). Different letters represent statistically significant difference between cadences for both execution forms (p ≤ 0.05). *represents statistically significant difference between execution forms (p ≤ 0.05).

According to the results, the cadence significantly influenced all the variables, and the values of the cardiorespiratory variables increased with the increase in cadence. Similar results are observed in exercise without horizontal displacement, such as water-based exercise. 1,12–14 Alberton et al. 13 found that cardiorespiratory responses (%HRmax and %VO2max) increased with increasing cadence during stationary running. The authors used the same cadences as those used in the present study, which were 60, 80 and 100 bpm. Similar results were observed by Raffaelli et al. 15 who evaluated the VO2, Ve, HR and RPE responses of five water-based exercises at different cadences (110–120 bpm, 120–130 bpm and 130–140 bpm) and observed a significant increase in these variables with increasing cadence.

In exercises with horizontal displacement, such as water walking, these results occur with increasing linear speed. 18,19,25–27 Hall et al. 18 evaluated the HR and VO2 responses during submaximal exercise on a water treadmill. The tests were performed at speeds of 3.5, 4.5, and 5.5 km h−1. The cardiorespiratory variables increased linearly with an increase in the speed of the exercise. Shono et al. 25 evaluated HR, VO2 and EE during water walking at speeds of 20, 30, 40 and 50 m min−1. The authors observed an exponential increase in these variables with the increase in speed.

These responses occur due to the increase in corporal velocity in relation to the water, which leads to a large increase in resistance. This greater drag force can be explained by the fact that the velocity (s) is squared and directly proportional to the resistance (R), which can be represented as a general fluid equation (R = 0.5. ρ A s2 Cd). 21 Thus, the increase in speed causes greater resistance to forward motion and, consequently, results in an increase in exercise intensity, maximizing the cardiorespiratory response and RPE.

Moreover, the results showed that the displacement effect significantly influenced the VO2, Ve and RPE variables, resulting in higher values for deep water running with displacement when compared to running without displacement. Deep water running performed with horizontal displacement results in a larger projected area than running without horizontal displacement, particularly as horizontal displacement involves the trunk segment as the projected area in addition to segments of the thigh and leg. Thus, as the velocity, the projected area (A) is also directly related to increases in the resistance to the advancement (R). 21

Similar results were found by Alberton et al. 28 who observed that responses for HR and VO2 were greater for water aerobics exercises with the greatest projected area in the same cadence of execution (60 bpm). The exercise frontal kick to 90° with horizontal shoulders flexion and extension showed significantly higher values, while the jumping jacks with arms pushing alternately to the front showed significantly lower values. The authors suggest that these responses are related to different projected areas of each exercise, different muscle mass involved and varying range of motion. In a study by Cassady and Nielsen 1 the authors observed that the subjects reached a higher intensity when performing water exercise, with the lower limbs at each cadence tested when compared to exercise performed with the upper limbs. The authors suggest that this result occurred due to greater lower limb length, representing a higher projected area in relation to the upper limbs.

However, Kanitz et al. 3 did not find a significant difference between deep water running with and without displacement in cardiorespiratory responses at a cadence of 80 bpm. The authors believe that, despite the increased resistance to exercise with horizontal displacement, the lower displacement velocity may have contributed to submaximal resistance, which influences the variables. However, in the present study, differences between the displacement forms were observed for all cadences, including 80 bpm. This difference between studies may be due to the higher sample size in the present study (12 subjects) compared to the results of Kanitz et al. 3 who recruited only six subjects.

Nevertheless, in the present study, HR did not show significant differences between the execution forms with and without displacement. It is believed that with a larger sample size (only seven subjects were available for analysis due to problems encountered with the HR monitor), we would have detected significant differences because the p value was marginally significant (p = 0.065).

Based on results from the present study, we can conclude that the cardiorespiratory responses and rating of perceived exertion can be maximized by increasing the performance cadence. Moreover, deep water running performed with displacement shows higher responses when compared to running without displacement for oxygen uptake, ventilation and rating of perceived exertion. Therefore, it is suggested that, according to the goals of a given deep water running class, instructors can use varying velocities and forms of displacement. For example, an interval class could alternate deep water running without displacement that has a perceived exertion of 11 (light – perceived exertion for the 60 bpm cadence) with deep water running with displacement that has a perceived exertion of 17 (very hard – perceived exertion for the 80 bpm cadence).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare to have no conflict of interest.

The authors specially thanks FAPERGS, CAPES and CNPq Brazilian Government Association for its support to this Project.